Issue 31, Spring 2018

In this issue

- FPOM - short SFS notes and quick links collected from "the drift"

- Last minute meeting info

- New FWS editor announced

- Article Spotlight - behind the scences look at Calhoun et al. 2018 FWS

- ITD Q&A - PhD student Brian Kastl mentors

- Dear Nick - great advice from Nick Aumen

- Meet a member - introducing 5 SFS random members you might not know

- SFS members participate at USA Sci. & Eng. Festival

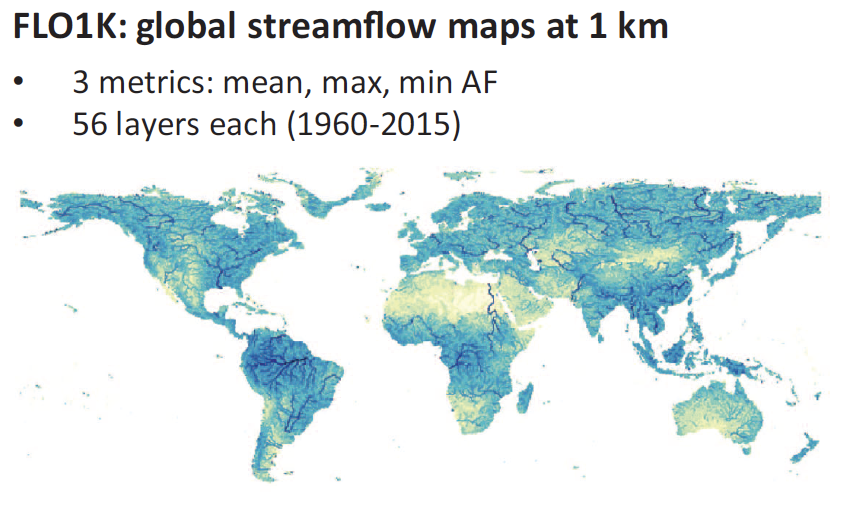

- Free data: a global streamflow map for freshwater scientists

Dear Society for Freshwater Science,

Your spring issue of In the Drift is here! That means we are counting the days to the 2018 SFS annual meeting in Detroit, aka the SFS “family reunion.” Take a look at the last minute meeting info for everything you need to be prepared for this big event.

I would like to thank Nick Aumen, Michelle Baker, Anna Boegehold, Amy Burgin, Dana Calhoun, Checo Colón-Gaud, Cliff Dahm, Ted Grantham, Kim Haag, Darrin Hunt, Brian Kastl, and Tiffany Schriever for their contributions. Fellow Public Information and Publicity (PIP) members Ayesha Burdett, Ryan Hill, and Eric Moody continued their support of In the Drift.

Hope you enjoy this issue and I'm looking forward to seeing you all in Detroit!

Ross Vander Vorste, editor

VanderVorste.Ross@gmail.com

FPOM

Short SFS notes and quick links collected from "the drift"

- FWS seeks part-time technical editor

- A new Making Waves episode with J. Kolby, N. Roach, and M. Whiles discusses neotropical amphibian conservation

- Teaching higher-ed? Olden Lab seeks your input by May 17, 2018

- Stay Fresh! is your source for new papers in the field of freshwater sciences

Last minute meeting info

Headed to Detroit? Be prepared!

- Find your presentation time here [presentation search]

- Lodging addresses and phone numbers [nearby hotels]

- Food, drink, and entertainment guide by SFS's Anna Boegehold and Darrin Hunt [visitor's guide]

- Uploading your presentation [presenter info]

- Meeting schedule [agenda]

- SFS updates Code of Conduct

Judges are still needed for this year's student presentations and posters. Judges are especially needed for Thursday afternoon and the poster session. Please consider volunteering your time and providing valuable feedback to our student members. To volunteer contact Peggy Morgan - pegrat307@msn.com

New Freshwater Science editor announced

By Michelle Baker

The Society for Freshwater Science is pleased to announce the appointment of Charles "Chuck"" Hawkins as Editor of our journal Freshwater Science. Chuck brings a 40-year personal history with, and commitment to, the society and journal.

He said he is excited about the opportunity to promote content that emphasizes interdisciplinary approaches to understanding and managing freshwater ecosystems and their biodiversity. Chuck takes the helm of our society’s flagship publication immediately and will overlap for a month with Pam Silver who has been Editor for the past 13 years. "We are so grateful for Pam‘s amazing hard work and the dedicated way she has shepherded our journal, especially through the changes in its name and scope in recent years,” said Colden Baxter, President of SFS. “With Chuck Hawkins stepping into this role, we know we have another committed member of our community providing the skills and leadership needed to take the journal where it needs to go."

Chuck mentioned that some behind-the-scenes changes are occurring in journal operations, including the hiring of a technical editor, but authors and readers should expect to see the same level of outstanding service that the editorial staff and the University of Chicago Press provided in the past under Pam’s leadership. He looks forward to working with the Editorial Board to identify and recruit exciting content and grow the quality of the journal. Chuck can be reached at fws.editor@freshwater-science.org.

Article Spotlight

By Ross Vander Vorste

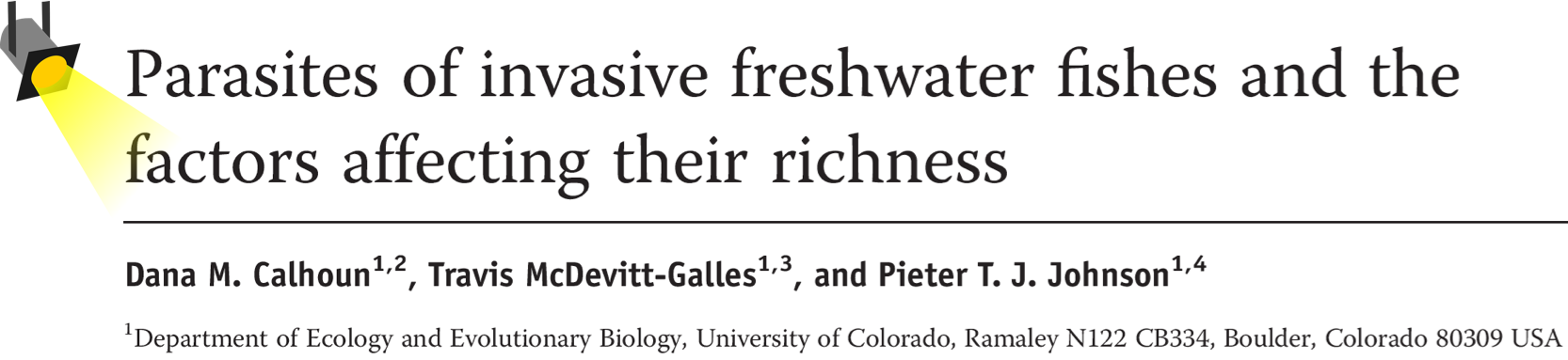

Calhoun et al. (2018), Issue 37(1):134--146

Parasites…Ew!…Dead fish…Ew!! These were my thoughts when I spoke with Dana “Dain” Calhoun about her new FWS paper. Dain and colleagues at the University of Colorado Boulder deserve an episode of “Dirty Jobs” for their work describing parasite communities in invasive fish they collected from California ponds.

Dana Calhoun searching for parasites on an invasive fish

The goal of this study was simple; the work to achieve it was not. Dain and colleagues wanted to shed light onto the prevalence, abundance and richness of parasites infecting the invasive fish species which dominate natural and artificial pond ecosystems in California. Broadly, parasites are organisms that live off of other organisms (i.e. their hosts) and include macroparasites like flukes (Trematoda) and roundworms (Nematoda). Scientists are just beginning to understand the many ways these parasites can affect host behavior and morphology. For fish and other aquatic organisms, parasite infection can alter behavior in ways that increase host susceptibly to predation which, in turn, helps transmit parasites to final hosts including mammals and birds. Growing evidence suggests invasive fish species may be more susceptible to parasites than natives. However, freshwater ecologists have often ignored parasites because of their diversity and the difficulty in their collection and identification.

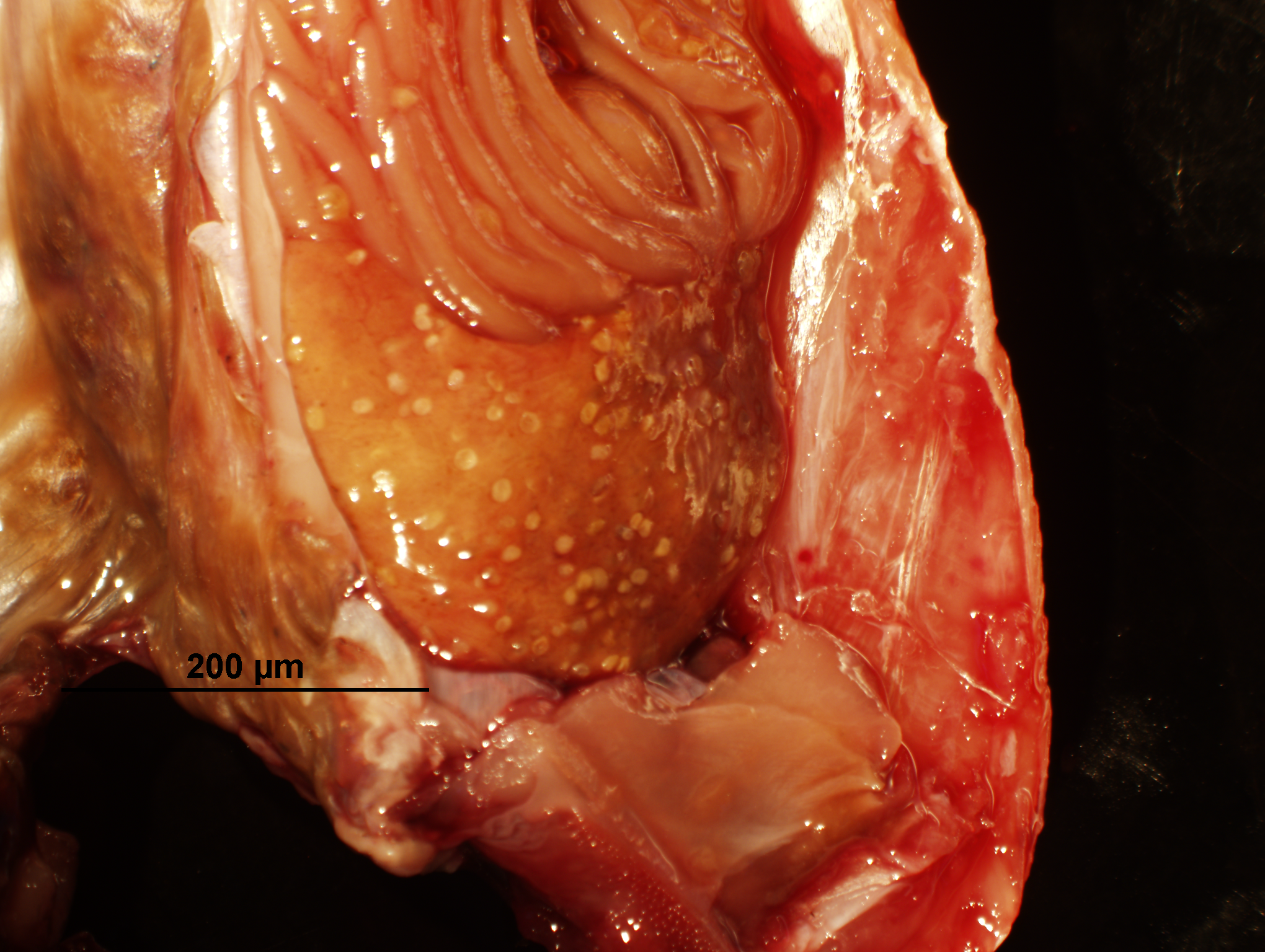

Processing one fish for parasites can take an experienced parasitologist an entire day. Impressively, Dain and colleagues processed over 700 fish in this study. First, the eyes, nares, internal organs, muscles, and gills were dissected in search for parasites barely visible with the naked eye. Gills were thoroughly washed in test tubes to dislodge parasites and lateral-lines, which allow fish to detect pressure and vibration, were removed and examined. If this process was not involved enough, imagine the added pleasure of doing it with your nose just inches over a decomposing fish carcass. As the hours pass, the smells only get worse.

When Dain mentioned “one tech working in the lab had to wear nose plugs to avoid the smell,” I said to myself, “only one?”

Once parasites are removed the work is not done. Dain and her dedicated technicians identified them on the fly under a microscope. They saved individuals for staining on slides and molecular analysis, which could thankfully be done away from the dead fish. Archiving these pesky parasites was important considering they had not been studied in California fishes this broadly since 1953. Across 27 ponds, Dain and colleagues identified 14 parasite taxa in six fish species ranging in size from tiny mosquito fish to lunker catfish over the course of 3 years. Their work discovered 16 new host records and 5 new geographic records.

Trematode, Posthodiplostomum minimum, was the most common fish parasite in this study, seen here as pale spots in the fish cavity

If you are an invasive fish in California, chances are good that you carry some parasites. Even the family goldfish that was “let free” in the nearby pond was parasitized. Dain and colleagues found that larger fish, such as large-mouth bass, had more parasites, in terms of richness and raw abundance, than smaller fish. This result was consistent with previous studies and Dain and colleagues explained the host size-parasite relationship by larger fish having more surface area, longer lifespans, and more frequent interactions with prey items that may also host parasites. Along with body size, parasite richness was correlated with pond size, water quality, and richness of other free-living fauna, such as amphibians, crustaceans, and insects.

In our conversation, Dain also described challenges during this project in the field. Notably, California’s historic drought dried up seven of their study ponds midway through the project. This was bad news for their data collection but good news in that invasive fish from these ponds were extirpated. Dain and colleagues continue to assess many of the ponds in this study as part of long-term efforts to understand amphibian declines.

Things were not all bad for the field crew in California, led by Travis McDevitt-Galles, considering they got to spend time capturing invasive fish using the rod and reel method. So “dirty job” or “dream job,” you take your pick.

Collecting invasive fish using the ol' rod'n'reel method

Dain and colleagues work has real implications for pond biodiversity in California and throughout the West. The fact that many invasive fish inhabiting these ponds can sometimes have thousands of parasites brings greater importance to understanding their interactions with native species. As discussed in the paper, negative effects of parasites on invasive fish could easily “spillover” onto native populations and the ecosystem functions they support. Despite their tiny size, parasites have been linked to mortality and malformation of native amphibians. Dain is excited about future work in the Pieter Johnson Lab that will continue to investigate parasite-driven spillover effects and changes in host behavior. We at SFS look forward to reading more from them.

If you are interested in reading more you can find the article here [Calhoun et al. 2018], visit the Pieter Johnson Lab website, and see their growing list of parasites and hosts [parasite database].

Email your recommendations for the FWS Article Spotlight to VanderVorste.Ross@gmail.com

ITD Q&A

Brian Kastl - PhD student, UC Berkeley

Brian Kastl is an outdoor educator for National Geographic (Nat Geo) Student Expeditions and a UC Berkeley PhD student in the Grantham Lab. He has taught and mentored emerging conservation leaders from around the world to solve pressing issues in freshwater science. I asked Brian a few questions about his experiences and how they have helped his own research that aims to bring coho salmon from the brink of extinction and into the lives of Californians.

Brian Kastl mentoring students to help solve complex conservation issues.

- Tell us about your experience leading outdoor environmental education expeditions

Since I began using the Rocky Mountains as a “classroom” to teach hydrology, I knew that outdoor education offers something special. So I became a National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS) instructor to customize teaching approaches to the individual learning styles and conservation passions of my students. I’ve particularly enjoyed mentoring student-driven projects on land-sea connectivity in Belize, as a Nat Geo Student Expedition leader. This summer, I’ll raft the Nenana River in Alaska for Nat Geo with middle school students, so they can experience first-hand the migration of coho salmon: a key species for land-ocean connectivity. I look forward to showing them how I use integrated transponder technology to monitor coho migration to the Pacific Ocean.

- What do you enjoy most about mentoring?

I love seeing students’ excitement as they discover their greatest interests in our water-driven world. They are the explorers, and I try to support the incubation of their individualized research projects. I’m thrilled that our Cambodian students, funded by a US State Department Grant with the East-West Center, went on to develop a community-based group that restores hydrologic connectivity in a Cambodian mangrove forest. Our other students went on to develop the Middle East Environmental Leadership Program in Palestine, where I was honored to cut the opening ceremony ribbon and judge the merit of innovative water conservation technologies. One of the winning teams developed a device that extracts drinking water from low-humidity air to reduce diversions from local streams.

- How can outdoor education help the field of freshwater science and conservation?

Long-term support and strides in freshwater science can be enhanced through outdoor education of students interested in a range of academic topics. I tell my students that freshwater conservation is a highly interdisciplinary field and that we need more than only natural scientists to protect aquatic habitat. We need psychologists to understand how outdoor experiences improve mental health, lawyers to establish protected areas, and the list goes on. Ultimately these individuals will reach the public and policy makers, whose support is essential in ensuring that our freshwater science findings inform freshwater conservation.

- What is most rewarding, as a graduate student, about outdoor education?

Watching our students grow as freshwater science leaders is immensely rewarding. I’ve also enjoyed participating in an innovative field-based course myself. The first UC (University of California) Water Academy explored rivers, lakes, dams, as well as sites of ecological and flood mitigation co-benefits. It takes experiencing the sites to fully understand the gravity of water management impacts on ecological processes. Speaking with a variety of stakeholders – farmers, dam operators, and conservationists – helped me to refine my language to more effectively communicate my own research that uses cutting-edge technology to measure conditions experienced by coho salmon. This field course, much like my experience as an outdoor educator, informed my own PhD research direction, honed my career goals, and connected the public with the freshwater science community in a meaningful and lasting way

Undergraduates from Myanmar, Philippines, and Malaysia learn about wetland restoration near Chesapeake Bay (photo by Brian Kastl).

Dear Nick - Advice from Nick Aumen

DEAR NICK: I am very excited that my first SFS annual meeting is just around the corner, but at the same time, I am feeling nervous. I want to get the most out of this opportunity to network and to learn, but I am an introvert. How do I make the most out of this chance to meet experts in my area of interest and to develop new contacts and professional relationships? – ANXIOUS BUT HOPEFUL.

DEAR ANXIOUS: Your nervousness is completely normal for anyone in your situation – introvert or not. But, you should know that SFS meetings and SFS members are notoriously open and accommodating to students and early career professionals. And, the society has a very active Student Resources Committee (SRC) and several events catering to students, such as the SRC Student/Mentor Mixer, the Early Career Mixer and lunch workshops, and the general mixers each evening. The mixers and the coffee breaks are great opportunities for you to meet and interact with prominent and influential scientists interested in the same topics as you.

For starters, I bet there are well-known and well-published scientists who will be at the meeting that you know through your literature searches and by their reputations. Make a point to find them during the meeting, introduce yourself, ask them questions about your research, and see if they would be willing to communicate with you during the course of your program. If you are too nervous to approach them directly, ask your advisor or another mentor to help make the introduction. Another approach is to attend a talk (or poster) they give, and approach them after the session. I have found that a good way to develop networks is to present a poster instead of a talk. It provides the opportunity for one-on-one conversations with those that are interested in your subject. No matter how famous you think they are, or how accomplished they are, I promise you they will take the time to interact with you – that is one thing that makes our society so special. Perhaps set a simple goal for yourself of meeting at least one such person each day of the meeting.

I remember my hesitation to do this as a student at my first meetings, and the only way I overcame my hesitation was to just do it, despite my nervousness and awkwardness. After the first couple of times, I became more relaxed and realized these folks are just normal human beings, happy to contribute to the development of your career as a scientist. When I was a brand-new faculty member, I garnered enough nerve to introduce myself and speak with a NSF director at a mixer, floated an idea I had, and ended up with seed money to conduct a workshop on stream solutes the following year thanks to this person’s genuine interest and support from that first meeting.

Finally, it may be important for you as an introvert to find ways to stay energized when you are surrounded by 1,000 people over the 4-5 days of the meeting – it can be overwhelming and exhausting. Schedule enough quiet time to recharge your batteries. Perhaps exercise is your thing, or plan for a meal alone in your hotel room. I like to spend a few hours exploring the local area by myself as a way of breaking up the day. Whatever you choose to do, enjoy your time at the meeting, and let that time inspire, motivate, and energize you!

Meet a member

Introducing 5 SFS members you might not know

These 5 SFS members were chosen at random from our membership directory. They highlight the diversity of our membership in terms of backgrounds, research interests and career stages. Feel free to connect with these members and maybe share a drink with them at the next conference.

Amy Burgin -- aquatic ecosystem ecologist/biogeochemist

- What is your field or topic of study?

I am an aquatic ecosystem ecologist and biogeochemist with a particular fondness for the nitrogen cycle. I want to understand how climate change and ecosystem restoration impact water quality in agricultural landscapes.

- Summarize your current and past roles.

I am currently an Associate Professor/Associate Scientist at the University of Kansas and Kansas Biological Survey; I've been at KU since Jan. 2016. I did my Ph.D. at Michigan State (2007) and a post-doc at the Cary Institute (2009) before taking faculty positions at Wright State University and the University of Nebraska.

- What is something you are passionate about related to freshwater science (or not)?

I am passionate about helping others learn how to effectively communicate science. I was a speech and theater nerd in high school and college, so I like being able to combine my love of science and love of communicating. I am also passionate about undergraduate research opportunities; I went to a small liberal arts college and was a first-generation college student. Thus, I had no idea that research was a thing you could do (and get paid for) until I had an REU at Hubbard Brook. Now, I try to open the doors to science for as many undergrads as possible.

- Which scientific paper, book or other media has inspired you?

I was an undergraduate when the Lotic Intersite Nitrogen eXperiment paper came out in Science (Peterson et al. 2001 Science). This paper was hugely important in my decision of what to study in grad school. The LINX 1 & 2 collaborators were instrumental in my career; what is the most inspiring is seeing (and being trained to work in) truly collaborative, supportive groups tackling big science that can't be done by a single person.

- Where can we find out more about your science?

Twitter is where you can find recent musings and field pictures: @burginam. I try to update my website once a year, found here

- How long have you been a member?

My first meeting was in 2003 (Athens, GA). I remember a great peach cobbler and line dancing at the banquet and learning what a "swamp cooler" was from staying in the UGA dorms.

- Will you attend the SFS meeting? Where can we expect to find you?

Yes, I'm so excited to be going back to Michigan! You'll find me in the Biogeochemistry sections.

Cliff Dahm -- ecosystem ecologist

- What is your field or topic of study?

Depending on the context, I give my field of study as ecosystem ecology, aquatic ecology, or biogeochemistry.

- Summarize your current and past roles.

I have been a teacher, a researcher, a mentor, a principal investigator, a program director, and a lead scientist. Currently, I am semi-retired and focusing on completing past research, serving in some advisory and synthesis roles, and being part of our hydrogeoecology group at the University of New Mexico.

- What is something you are passionate about related to freshwater science (or not)?

I am passionate about communicating aquatic science to decision makers, politicians, and resource managers so that our science is used in the important decisions of how we allocate and manage water.

- Which scientific paper, book or other media has inspired you?

My background is in oceanography before I transitioned to freshwater science so I was inspired by the work of Al Redfield and in particular the Redfield, Ketchum, and Richards 1963 article in the book "The Sea" found on pages 26-77.

- Where can we find out more about your science?

I am not maintaining a website anymore, but you can contact me directly at cdahm@unm.edu.

- How long have you been a member?

I joined the North American Benthological Society (NABS) in 1984 as I transitioned from the Stream Team at Oregon State University to my faculty position at the University of New Mexico and the Hydrogeoecology Group there.

- Will you attend the SFS meeting? Where can we expect to find you?

I will miss the annual meeting in Detroit this year as I will be in Spain serving on a science advisory committee and visiting colleagues in Catalan and the Basque Country. I look forward to the annual meeting in 2019 in Salt Lake City!

Ted Grantham -- ecohydrologist

- What is your field or topic of study?

I am interested in how water management affects freshwater ecosystems in the context of climate change. The goal of my research is to identify solutions that allow people and freshwater organisms to coexist in a hotter and more volatile climate future!

- Summarize your current and past roles.

I am currently a cooperative extension specialist and assistant professor in the Department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at U.C. Berkeley, where I also received my PhD. Prior to this position, I was a Mendenhall postdoctoral researcher at the USGS Fort Collins Science Center. I also spent two years as a postdoc at the U.C. Davis Center for Watershed Sciences and one year as a Fulbright Fellow at the University of Barcelona.

- What is something you are passionate about related to freshwater science (or not)?

There's no place I'd rather be than on a river (which also happens to be the name of my son).

- Which scientific paper, book or other media has inspired you?

Totem Salmon by Freeman House made me realize the inherent connection between people and nature and why it is important to keep wild things alive on our planet.

- Where can we find out more about your science?

Check out my website!

- How long have you been a member?

The first SFS meeting I attended was in Santa Fe, New Mexico in 2010. I've been a member ever since!

- Will you attend the SFS meeting? Where can we expect to find you?

I look forward to the meeting in Detroit! You'll find me catching up with old friends and participating in the climate change sessions.

Kim Haag -- freshwater ecologist

- What is your field or topic of study?

My field of study is freshwater ecology, principally streams, rivers, and wetlands.

- Summarize your current and past roles.

I work for the U.S. Geological Survey. I began my work in the National Water Quality Assessment Program in Kentucky and in south Florida. I later transitioned to interdisciplinary studies in isolated freshwater wetlands.

- What is something you are passionate about related to freshwater science (or not)?

I care deeply about communicating environmental science to the general public in a way that can effectively influence decision-making and public policy.

- Which scientific paper, book or other media has inspired you?

The Ecology of Running Waters by Noel Hynes inspired me because it was the foundational text for stream ecology, and because I was fortunate enough to meet the author.

- Where can we find out more about your science?

https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1342 https://pubs.usgs.gov/pp/1758/ https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/cir1207

- How long have you been a member?

40 years (since 1977)

- Will you attend the SFS meeting? Where can we expect to find you?

Yes I will attend; Finance Committee meeting, Board of Directors meeting, annual Business meeting, wetlands sessions.

Tiffany Schriever -- wetland ecologist

- What is your field or topic of study?

I am a wetland ecologist that studies community and food-web dynamics of aquatic macroinvertebrates and amphibians in temporary wetlands.

- Summarize your current and past roles.

I am an assistant professor in biology at Western Michigan University where I teach, conduct research in rare interdunal wetlands along Lake Michigan’s lakeshore, and supervise four graduate students. My last role was a post-doc in Dr. Dave Lytle’s lab at Oregon State University examining how aquatic insect biodiversity is maintained across desert landscapes..

- What is something you are passionate about related to freshwater science (or not)?

I am passionate about understanding all things connected to temporary waters including which organisms live there, how they live there, how they interact within the food web, how diversity and distribution are with changing with climate, and how temporary systems are connected to the terrestrial matrix surrounding them.

- Which scientific paper, book or other media has inspired you?

Food Webs: Integration of Patterns and Dynamics co-edited by Gary Polis and Kirk Winemiller. David Post – all of his food-web structure and stable isotope work. Kirk Winemiller's papers are essential reading about integrating natural history, long-term field studies and understanding diversity in food webs. The ecology of temporary waters by D. Dudley Williams

- Where can we find out more about your science?

Website needs an overhaul but here it is

Or find me in the WMU bio page

Current grant publicity

- How long have you been a member?

One year

- Will you attend the SFS meeting? Where can we expect to find you?

Yes! I will be co-presenting a poster (Dragonfly and damselfly (Odonata) biodiverisy in interdunal wetlands at Saugatuck Harbor Natural Area, Michigan) with a WMU undergraduate and introducing my graduate student (hopefully with beer in hand) to all the awesome folks of SFS!

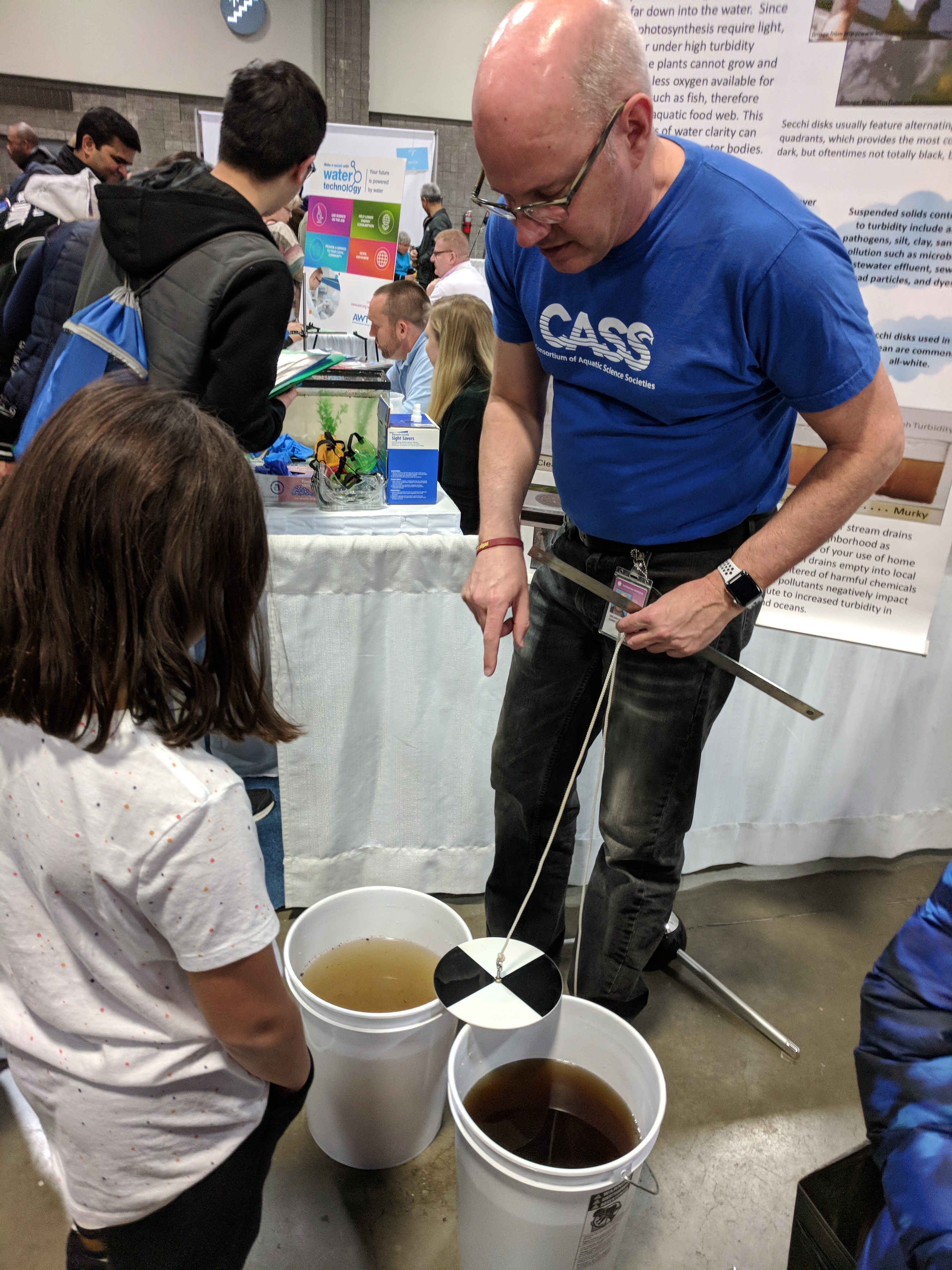

SFS members participate at USA Science & Engineering Festival

SFS members teamed up with the Association for the Sciences of Limnology and Oceanography (ASLO) to represent the Consortium of Aquatic Science Societies (CASS) at the 2018 USA Science and Engineering Festival in Washington, D.C. held on April 7-8, 2018. According to the ALSO communications office, about 3,300 young, scientists, parents, teachers, and adults attended the festival. A CASS booth, organized by Adrienne Sponberg (ASLO), offered hands-on activities covering key concepts in aquatic sciences. Those that visited the CASS booth left with a greater appreciation for water resources. CASS plans a similar booth at next festival in 2020.

CASS volunteer demonstrates the Secchi disk to students

Free data

Looking for historic streamflow data? Try FLO1K!

The In the Drift newsroom recently came across a global map of annual streamflow data generated at 1 km resolution. The FLO1K map contains information on mean, maximum and minimum annual flows at the global-scale from 1960-2015. Best of all, it is free for your integration. Surely, us freshwater scientists will see tremendous potential here!