In the Drift: Issue 30, Winter 2018

In this issue

- FPOM – short SFS notes and quick links collected from “the drift”

- Article Spotlight – Behind the scenes look at Bogan 2017 FWS

- A tribute to SFS hero Andy Sheldon (1938-2017)

- Pam’s Journal Notes – a farewell from our editor-in-chief

- ITD Q&A with SFS Executive Director Andreas Leidolf

- Dear Nick – great advice from Nicholas Aumen

- SFS Chapter meeting recap from California

- SFS Chapter meeting recap from the Pacific Northwest

- SFS members participate in STEM conference

- New Special Issue on river metacommunities – led by SFS member

Dear Society for Freshwater Science,

Happy New Year! I hope that everyone celebrated the end of 2017 and is off to a great start this new year. There is so much to be excited for as members of SFS. In 2018, we have the opportunity to visit Detroit, the “Motor City,” for our annual conference or possibly make a trip to Ecuador for AQUATROP, a meeting co-organized by SFS and three other societies. There will be no shortage of opportunities to hang out with your favorite freshwater colleagues and present your research.

As our SFS president, Colden Baxter, describes in his President’s Environment, there are exciting changes occurring within the Society. One major change is the resignation of Pamela Silver, editor-in-chief for Freshwater Science. This In the Drift issue features a heartfelt farewell from Pam that I encourage you to read. The Society is thankful of her for taking the journal to new heights and truly sad to see her go. The exciting part is that SFS will be hiring someone to take her place.

This issue’s Article Spotlight highlights a paper by Michael Bogan. Michael’s research on the peculiar stonefly featured in this paper goes back 10+ years and makes for an inspirational story for all of us “bug-lovers.” This issue is bursting with other insightful freshwater news. I thank all those that contributed content including Nicholas Aumen, Michael Bogan, Checo Colón-Gaud, Deb Finn, Jeannette Howard, Bob Hughes, Andreas Leidolf, Dorene McCoy, Francine Mejia, Pam Silver, and Jonathan Tonkin.

Enjoy your winter issue of In the Drift,

Ross Vander Vorste, editor

FPOM

Short SFS notes and quick links collected from “the drift”

- Job opportunity: SFS editor-in-chief, must apply before 18 February (announcement)

- SFS president Colden Baxter discusses changes to the Society and progress towards our goals in his President’s Environment.

- Abstract deadline for the 2018 SFS meeting in Detroit extended to 5 February (abstract info here)

- SFS Endowment awards are available for graduate and undergraduate students with applications due 31 January.

- Class is in! The Instars undergraduate mentorship program for under-represented groups is recruiting their 8th class. Potential fellows must submit applications by 2 February and mentors by 23 February.

- The latest Making Waves podcast features Dr. Amanda Subalusky, postdoc at the Cary Institute, discussing the influence of animal movement and behavior on whole ecosystem function.

Upcoming meetings announcements

Tropical Aquatic Ecosystems in the Anthropocene (AQUATROP) - Focus on tropical freshwater ecosystems in the context of major changes that are occurring due to human interventions. Quito, Ecuador, 21-27 July 2018. Abstract submission now until 28 February (more info).

4th International Symposium of the Benthological Society of Asia and 2nd Youth Freshwater Ecology School - Contributing useful solutions for improving the health and biodiversity of Asia’s freshwater ecosystems. Nanjing, China, 21-25 August 2018 for meeting, 19-20 August for ecology school. Abstract submission 12 Febuary-22 April (more info)

Benthic Ecology Meeting Society (BEMS) - Exchanging scientific information on marine benthic ecosystems (e.g., rock intertidal, coral reef) and fostering the next generation of benthic biologists. Corpus Christi, Texas, 27-30 March 2018. Abstract submission now until 16 February (more info).

Article Spotlight

By Ross Vander Vorste

Bogan, 2017, Issue 36(4): 805-815pgs.

Picture a man riding a bicycle through the city of Tucson, Arizona with a bug net in hand and a smile running cheek to cheek. This man was Dr. Michael Bogan (Assistant Professor at University of Arizona) during the winter of 2016/2017 as he excitingly collected his favorite freshwater invertebrate, Mesocapnia arizonensis (aka the Arizona snowfly). But finding the Arizona snowfly was not always so easy for Michael as I learned in a recent video chat with him. We discussed his newest article about this intermittent stream specialist published in Freshwater Science.

To tell the story behind Michael’s article and of his obsession with this stonefly we have to go back 15 years, when Michael was still a Master’s student at Oregon State University (OSU). Michael was making frequent 24-hour road trips from Oregon to Arizona to study aquatic invertebrates in arid-land streams where he was mostly finding lentic invertebrate assemblages, such as Coleopterans and Hemipterans, in isolated stream pools. However, Michael showed up in spring 2004 and to his surprise found his study sites flowing and, as he says, “all those lentic species were gone…instead I found midges, blackflies and stoneflies.” In one of his most intermittent sites named West Stronghold Canyon, a stream that had been dry for the previous 2 years, he found thousands of tiny (5mm length) emerging stoneflies causing him to exclaim “what the … is this?” It turned out that Michael’s close eye and persistence helped him discover a new population of the rare Arizona snowfly, a species that only emerges in the winter/early spring.

The majestic Arizona snowfly (Mesocapnia arizonensis) emerge as tiny adults (5mm length) after several years of dormancy in arid-land intermittent streams. Photo by Michael Bogan.

It was not until 2007 before Michael could return to Arizona to search for his newly beloved stonefly as an OSU Ph.D. student. He was determined to focus his project on the ecology and life history of M. arizonensis. Unfortunately, after several more road trips he only found his study sites in isolated pools and depauperate of stoneflies. This apparent disappearance of the Arizona snowfly caused Michael to rethink the focus of his Ph.D. and forget, temporarily, about the species.

Then came El Niño, a weather phenomena poised to bring flowing conditions back to Michael’s study sites and hopefully the reappearance of M. arizonensis. In 2010, Michael and his Ph.D. advisor, David Lytle, geared up for an intense sampling effort that included broad field surveys and genetic analysis aimed at describing the distribution and population connectivity of this enigmatic stonefly. This massive effort revealed a much broader distribution of M. arizonensis than expected, in fact, Michael was able to find the species in 45 new locations. Additional surveys found populations all across Arizona and into California. Furthermore, Michael’s relentless search helped discover that more geographically isolated populations of M. arizonensis showed more genetic distance from one another, indicating a relatively weak dispersal ability.

Then came El Niño, a weather phenomena poised to bring flowing conditions back to Michael’s study sites and hopefully the reappearance of M. arizonensis. In 2010, Michael and his Ph.D. advisor, David Lytle, geared up for an intense sampling effort that included broad field surveys and genetic analysis aimed at describing the distribution and population connectivity of this enigmatic stonefly. This massive effort revealed a much broader distribution of M. arizonensis than expected, in fact, Michael was able to find the species in 45 new locations. Additional surveys found populations all across Arizona and into California. Furthermore, Michael’s relentless search helped discover that more geographically isolated populations of M. arizonensis showed more genetic distance from one another, indicating a relatively weak dispersal ability.

So where does the Arizona snowfly hide from freshwater scientists like Michael Bogan the majority of years? Michael told me his attempts to rehydrate the dry sediments of West Stronghold in the laboratory were futile – no stoneflies. In addition, the water table in many of the streams where M. arizonensis is found can drop 20-70-m below the streambed surface so they are unlikely to remain active in the hyporheic zone. Instead, Michael hypothesizes that the organisms enter a diapause stage somewhere > 1-m below the surface and remain there until flowing conditions return in the streams. Thus, in order to find M. arizonensis, timing is key. Michael says “they are first in line… they get through their life cycle and they get out (emerge)” within a 6-8-week period. Although this life cycle is not unique, it is rare among the stonefly group, making it an intriguing species to study in the context of global change. Michael is happy now that he is permanently located in Arizona where, when the conditions are right, he can simply hop on his bike to go visit his invertebrate “besties.” Michael hopes that he and his students can continue working with M. arizonensis in the field and laboratory to better understand its life history and ecology.

Bear Canyon, Arizona is one of the many streams where the Arizona snowfly (Mesocapnia arizonensis) was collected, shown here during February 2013. Photo by Michael Bogan.

You can find much more about the Arizona snowfly’s life cycle and distribution in Michael’s Freshwater Science article. As he points out, this species seems ready to handle global change in the 21st century (to a certain degree), which will likely bring more droughts and water abstraction to arid-land regions. Therefore, you can think of his article as a “feel good” story when most of our focus is on impending losses of freshwater biodiversity.

Have another great Freshwater Science article that you think should be featured in the ArticleSpotlight? Send your recommendations to vandervorste.ross@gmail.com.

In memory of an SFS Hero

Andy Sheldon (1938-2017)

By Deb Finn

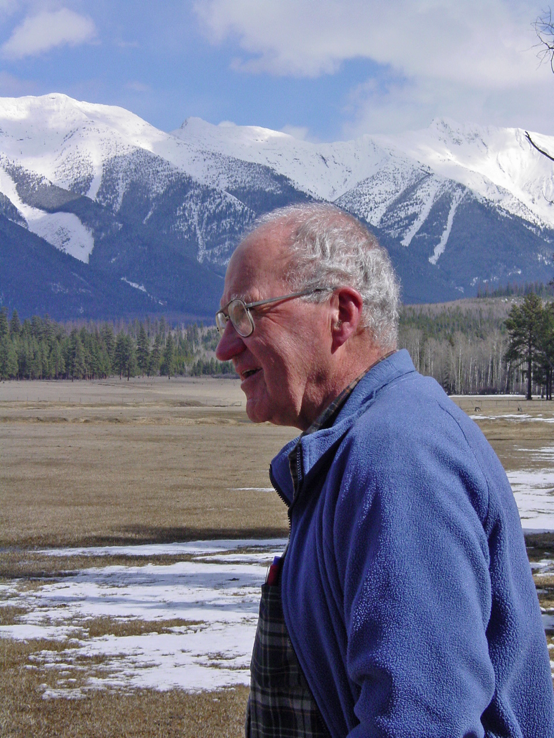

Andy Sheldon in the Seeley/Swan, Montana, after he retired from U of M. Photo: Erick Greene.

SFS lost an incredible scientist, friend, and stalwart mentor when Andy Sheldon passed away on Nov 25, 2017. On behalf of “Team Sheldon” (a nonrandom sample of folks close to Andy), I agreed to write a memorial for In the Drift. It has been a difficult task, and I lean heavily on contributed anecdotes and photos from a subset of Andy’s friends and colleagues spanning 50+ years – from grad school at Cornell in the 1960s to now. The wonderful anecdotes follow and bring to life these brief descriptions of the roles that Andy played as a stream ecologist and SFS member:

Andy as mentor. Andy was the essence of “mentor”, and this one comes first because it was the most important to me, personally. Andy attended a NABS talk I gave in 2000 at Keystone. I was burned out, about to finish my MS, and planning my escape from academia. Andy spent an hour with me after my talk, suggesting statistics and pointing out exciting new angles to my research. I left Keystone a different person, a scientist ready to start a PhD and make my own contributions to stream ecology, and Andy and I became longtime “science pen pals”. I was not Andy’s only informal mentee, not by a long shot. Andy embodied the selfless spirit of NABS/SFS by continually reaching out to young researchers in which he magically detected a true love for streams and an uncanny drive to understand them (often with gold star for an inclination towards masochistic fieldwork and/or stoneflies!). He then took us under his wing for life. Not for credit, not for the tenure and promotion committee, but for the joy of streams, collaboration, and stoking the scientific campfire around which we all sit.

Andy as teacher. Andy loved teaching and particularly enjoyed his summer field courses at the Flathead Lake Biological Station, where he interacted with countless students and communicated his passion for science, fresh waters, and the “beasts” within (insects, fish and other critters). Andy taught at the University of Montana for 35 years and received the university-wide Distinguished Teaching Award there in 2003.

Andy as scientist. Andy was a role-model scientist who read the literature voraciously, including venturing well outside the range of his own specialty. He remembered and carefully applied what he read to his own work. As a result, Andy was the most well-rounded ecologist that many of us could think of. He was also continually engaged in science. Even in a Florida retirement (begun in 2003), he continued fervently both in “citizen science” (e.g. Florida Lake Watch) and in “scientist science” (continuing stonefly and fish projects). He often did this with his beloved wife Linda by his side, and he had no intention of slowing down. He was planning a 2018 field season, and Andy’s latest CV states “I have substantial unpublished backlog to occupy my spare time”.

Andy as writer. Andy wrote up his science succinctly, typically in short, declarative sentences without one wasted word. He was also a vocabulary guru. We spent substantial time arguing about obscure word meanings, and Andy always won. Read his papers. See for yourself. Like me, keep striving to “write like Andy”.

Andy as collaborator (“carpooler”). Andy was vocal about the importance of scientific collaboration. His final sole-authored paper (2016, Biodiversity and Conservation) is titled “Mutualism (carpooling) of ecologists and taxonomists”. Its final sentences embody the collaborative spirit and Andy in general: “Collaboration expands interests and blurs boundaries. Attend relevant meetings in the other discipline and read outside your field. Mutualism demands effort but continuity and reciprocity make carpooling work.”

Andy as penny-pincher. Andy was frugal and taught us that million-dollar NSF grants are not required for great science. He pieced together small grants to answer big empirical questions. Even as a tenured professor, he often camped on the outskirts of town to save money at SFS meetings. Take note, SFSters. Pursue the funds like mad, but do not let their absence keep you from the important stuff.

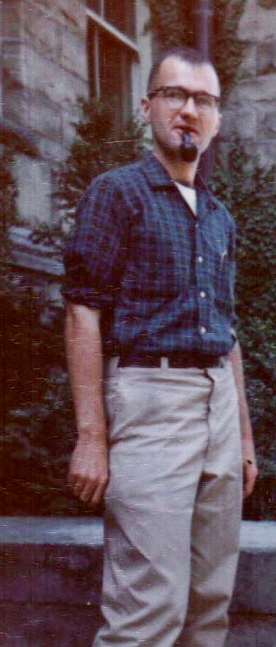

Andy as a PhD student on the front steps of Stimpson Hall, Cornell University in the mid-1960s. Andy was a student of Lamont C. Cole. Photo by fellow Cornell student Gregg Brunskill, with equipment he describes as "antique Kodak box camera". Of the pipe, another fellow grad student, Roger H. Green says, "I smoked a pipe sometimes, but it wasn't a trademark thing for me like it was for Andy".

| To help young SFSers embody Andy’s spirit, we have established an Endowment called the Andy Sheldon Fund for Field Ecology in Streams. It will eventually fund students doing field-based research in stream population or community ecology (Andy’s beasts) to attend annual SFS meetings. Awards can be made starting the year after the Fund’s balance reaches $10,000. Help us get there quickly by donating either directly through the online SFS Donations page [link] or by calling USU (SFS Member Services) at 435-797-0421 |

Andy anecdotes from a few friends, collaborators (“carpoolers”), and mentees

Jane Hughes, carpooler: Pete [Mather] and I took our children, Sally (12) and Andrew (10), to the University of Montana for a sabbatical in 1996. Andy introduced us to streams of the Bitterroot Mountains, which we walked up and down collecting stoneflies. Some hikes were over 20 km – one particularly memorable, where Pete and Andy only discovered that they had forgotten the collecting gear when they reached the top! We had to go back the next day and do it again. Andy’s enthusiasm for his ‘beasts’ and his streams was very infectious. After the trip, when we asked the kids about their highlights, Sally said ‘Disneyland’, and Andrew said ‘hiking up the rivers, collecting bugs with Andy’. Probably this was what led Andrew to help Bobbi Peckarsky in one of her famous mayfly experiments (when he was 14) then to go on to do a PhD in stream ecology and genetics. Salute, Andy.

Chris Funk, PhD advisee: Andy was an incredible mentor. As a scientist, Andy instilled in me the importance of knowing what other scientists before me had done, so as not to re-invent the wheel. He would regularly copy articles he thought I should know about and leave them on my desk. Andy also instilled in me the value of hard work, both in the field and in quality office time spent thinking deeply about research. There are many legends about what a hard worker (some say masochist) Andy was in the field. Perhaps most importantly, Andy taught me that to truly understand your study subject, you have to LOVE it. Andy loved rivers and the “beasts” that live in them. And Andy wasn’t just a great scientist. He was a deeply caring person who never lost the human touch. Early in my graduate career, a close fellow student died in a car accident. I was very upset, and Andy literally took my hand and said he was sorry for my loss. He also celebrated in my successes, and provided support through my failures. Andy taught me that great scientists can also be great people.

Winsor Lowe, “the guy who ended up in Andy’s position at U Montana after he retired”: My first interaction with Andy was memorable for me, but not very dramatic. In 1995, I had a job washing dishes in Bigfork and was trying to figure out how to get into grad school. Andy agreed to talk to me, so I drove down to Missoula and remember weaving through the stacks of books and samples in his office to get to his desk – which seemed on the verge of getting buried by all the stuff. He then gave me very succinct advice: apply to a person not a program, and read up on what people actually DO before making contact so you don’t come across as a dimwit. I have repeated that same advice to many students here at UM who are considering grad school, and I always tell them that it came to me from Andy – the person who had my job first.

Alicia Slater (formerly Schultheis), carpooler: I met Andy at my first NABS meeting (Keystone 1995). I asked him where he was staying and he pointed to the mountains, which is how I learned that he preferred to camp and eat peanut butter sandwiches to save money when he travelled. He also holds the record for the most times a collaborator has insisted that we rewrite a paper. I could never argue against it because his knowledge of the literature was encyclopedic. He was always learning, always curious, a guide, friend and mentor who will be sorely missed.

Scott Hotaling, recent SFS mentee who finished a PhD in 2017: I first met Andy in 2012 but already knew his work on mountain stoneflies. When I saw him the next year, I assumed he wouldn't remember me. Instead, he walked up and said "Scott, right?" and re-introduced himself as if I would be the one who wouldn't remember him. He then asked how things were going and I was honest -- I said things are good but it's been tough getting things done, that I felt like I was just spinning my wheels. He told me something like: "That's the way it goes. Everyone gets stuck. Just remember that you're doing important work and that it'll sort itself out if you keep at it." It did, of course, and that's a sentiment I've passed to others many times since. Later, it never failed that when I published a stonefly paper, I'd get a note from Andy -- "Hey Scott, I enjoyed your new paper! You're really getting the hang of this stuff" or something like that. When I defended last summer, I received an unsolicited book the same day – his monograph on the stoneflies of Nevada [with Baumann and Bottorff]. Inscribed on the inner cover was a note: "Onward! -Andy". Onward indeed, friend. You'll be sorely missed.

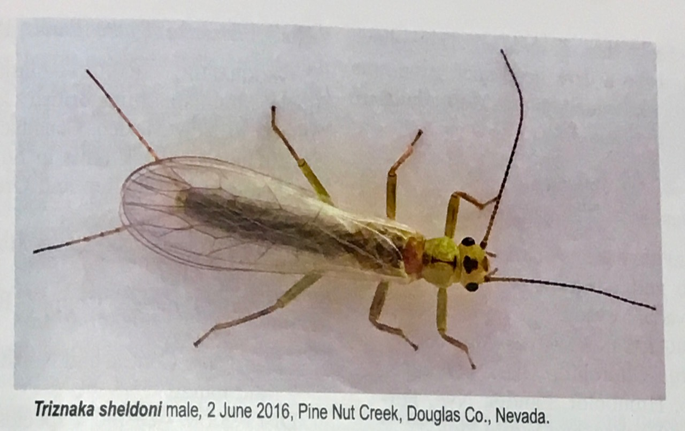

Triznaka sheldoni, one of six species named for Andy. Plecoptera became Andy's favored taxon after reading Jewett (1960) [link] in grad school. Photos from his culmination of 40 years of work in Nevada, just published as a monograph in 2017 [link].

For a more formal obituary, see [link]. If you are looking for more advice from Andy, see the SFS Article Spotlight in the Winter 2013 issue of in the drift [link].

Onward! Sincerely,

Deb Finn

Deb and Andy in Raleigh, SFS 2017. Andy had just informed me of the proper pronunciation of Moselia (after I had mangled it) and who that genus was named for (Martin E. Moseley, a volunteer at the London Natural History Museum). Photo: Jeremy Monroe.

Pam’s Journal Notes

By Pam Silver

In July 2017, after 25 years as a fulfilled faculty member, I found myself no longer able to decline requests to assume high-level administrative responsibilities at Penn State Erie, The Behrend College. I have finally learned the meaning of “totally maxed out”. I can no longer give the journal everything I have, and I won’t give it anything less. The best interests of the journal require that I resign at the end of volume 37 or sooner if the society finds a replacement for me.

When I was a graduate student, Rosemary Mackay was the face of the journal. At my first NABS meeting in Tuscaloosa (1988), Rosemary stood at the podium during the business lunch and gave the Editor’s report. She was straight-backed and dignified, and she exuded confidence. I wanted to grow up to be just like her. Rosemary taught me to write by editing 3 of my submissions to J-NABS. In 1997, Rosemary retired, Dave Rosenberg became the new Editor of the journal, and I made my way onto the Editorial Board. Dave mentored me through the processes of managing peer reviews, author revisions, and decision letters. In 2002, he asked me to become Co-Editor with him and Jack Feminella. I called Jack to express concern that I wasn’t ready, and Jack said, “If Dave asked you, he thinks you can do it.” I spent the next 3 years learning to meet Dave’s standards. His patience with my monumental stubbornness and my patience with his insistence on perfection occasionally wore thin, but he taught me to edit, and I cried when he retired in 2005. Dave gave me the confidence to apply for the position of Editor, and mentored me through the transition from Co-Editor to Editor.

Irwin Polls, Sheila Stephens, and the Editorial Board have supported me through a long journey with the journal. In 2006, Irwin redesigned the journal’s format and finances, and we switched to an online manuscript submission and tracking system. In 2008, we switched to online issue assembly, electronic proofs, and Ahead of Print publishing, and we revised BRIDGES. In 2009, I hired Sheila as a copy editor and assistant, and the 2 of us waded through the massive 2010 “Birthday Issue” together. We have been a team ever since. In 2011, the Editorial Board recommended that we change the title of the journal, and the society did that in 2012. In 2013, the journal left Allen Press and the University of Chicago Press (UCP) became our publishing partner. We reformatted the journal again, changed to Editorial Manager, and completely revamped our workflow. In 2014, we published our first issue with UCP (and aren’t the covers gorgeous?). In 2015-2016, we struggled with massive growth, and Irwin, Sheila, and I weathered the storm with a lot of support from Chuck Hawkins and the society and a lot of help from Kari Roane, Ashley Towne, and James Faber at UCP. Twenty-one years with the journal, and 13 years as Editor, is a good run. I am content.

Q&A with Andreas Leidolf, SFS Executive Director

By Ross Vander Vorste

SFS Executive Director, Andy Leidolf

If you’re like me, you have no idea what an Executive Director does for a professional society. Well, I asked our new and first Executive Director about his position in this edition of ITD Q&A. He was gracious enough to respond despite his long list of “to-do’s” for SFS.

ITD: Could you tell the Society about your background and how it brought you to serve as Executive Director for SFS?

Andy: I am an ecologist and wildlife biologist by training. I hold a B.S. in Forestry/Wildlife Management from Mississippi State University, as well as an M.S. in Wildlife Ecology from Utah State University. So, I have a pretty solid science background, and I have been involved in the conduct, transmission, and administration of scientific research for over 20 years.

For the past 3+ years, I have managed a statewide science collaborative focused broadly on research, training, education, and outreach in the area of water sustainability; and made up of over 800 current and former participants, 11 institutions of higher education, and over 100 partner organizations (http://iutahepscor.org/). I’ve immersed myself in the Science of Team Science, and participated in the inaugural 2017 cohort of the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Community Engagement Fellowship Program, which seeks to study, understand, advance, and formalize the emerging role of the scientific community manager. From these experiences, I’ve gained a real appreciation for building human capacity to facilitate large-scale, cross-institutional, interdisciplinary research.

Considering my interests in both science outreach and “inreach,” I think that SFS is a logical place for me. Scientific societies thrive on member engagement, and gain added meaning and relevance when they successfully connect their members’ science with relevant stakeholders and the general public. I really think that my experience and passion are well suited to SFS’s goals in this area, and apparently SFS’s Board of Directors thought so, too.

Tell us about your role as Executive Director? What types of projects will you working on for SFS?

I am charged with a number of routine administrative tasks related to SFS operations. This includes “exciting” stuff like reviewing and revising central planning documents; formalizing and executing workflows for SFS communications and archiving; participating in Annual Meeting preparations; and providing continuity and support for elected officer and standing committee membership transitions and turnover.

Additionally, I expect to play an increasing role in long-term strategic planning for SFS, particularly in the areas of member recruitment, diversification, engagement, and retention; long-term financial planning and development; and interaction with other professional societies.

As for specific projects I am working on right now, I have been working with Amy Marcarelli and Steve Thomas on revising the SFS Operations Manual. My vision is to eventually expand this document into more of a “Community Playbook” for our Society, but right now, I am focused on reducing redundancy with SFS bylaws; formalizing, standardizing, and aligning language, format, workflows and timelines. My goal is to make the Operations Manual more accessible to SFS officers, committee chairs, and members. I’ve also started participating in planning calls for Detroit 2018. This will be my first time attending the SFS Annual Conference and I couldn’t be more excited about the venue. I look forward to spending some time getting to know our large and diverse membership, so if you see me walking around, feel free to holler at me and introduce yourself.

What goals have you set for yourself or has the Society provided you related to your position as Executive Director?

It’s probably too early to talk specific milestones, particularly numeric, but nice try. In my defense, I am still looking for the paper clips! But seriously, as I ramp up my involvement and time commitment (I am scheduled to increase my position to half-time January 1, 2018), I look forward to participating and initiating discussions about meeting and exceeding the needs and expectations of our membership and growing and diversifying the SFS family. SFS should be more than just the logical place for freshwater scientists to connect—membership should be fun and rewarding and offer added value and lots of benefits. I would like to see the high level of engagement I’ve witnessed among our officers and committees continue to spread and grow across our entire membership, and sustain the excitement and flurry of activity that surrounds our annual meeting throughout the rest of the year.

I will help promote SFS’s engagement with stakeholders, the general public, and local communities where we hold our meetings or conduct other SFS activities. I am excited to work with SFS committees to make SFS more attractive, welcoming, and relevant to freshwater scientists outside the US and North America. We are an international society, but I believe there is much room to grow in our commitment to and involvement in freshwater science issues on a global stage.

What challenges do you envision associated with achieving these goals?

From an organizational perspective, I think time management and prioritization will be challenging. I know from experience that building broad, sustained, and meaningful engagement within and outside any scientific community is hard work, and it takes time.

On a more personal level, I should say that I have not always been very good at saying “no.” I want to be able to do all I can to help the amazing volunteers serving as SFS committee chairs and BoD members by serving on Standing Committees and in elected and appointed positions. So having to say “no,” on occasion, will be a challenge.

What impresses you most about SFS and why are you excited to be a part of this Society?

I have been quite impressed by the SFS culture, which is very close-knit, familial, intimate, and fun. People know one another and genuinely care about each other. For a small-ish organization, I am amazed at the sheer number of activities and initiatives that are happening across the SFS landscape. It’s unusual for a society with a membership of ~1500 to be so broadly and deeply engaged, and I think that really speaks to the quality of our membership and elected and appointed officers.

There are exciting new frontiers in the way scientists can (and should) engage with their stakeholders and the public. So, it’s not exactly a “boring” time to be scientist, given the current political climate, and I think SFS and its highly engaged membership is well-positioned to be a catalyst and a change maker in this arena. I am excited to be a part of that journey.

Dear Nick – Advice from Nicholas Aumen

DEAR NICK:

I am an early-career academic scientist hoping to make a better connection between my

aquatic research and policy decisions. I make sure my science is relevant to important

environmental policy issues, but I do not know how to bring my work to the attention of

policy-makers. What can I do to increase the science/policy connection in my research

program? This topic was not something that was covered well in graduate school.

– HOPING TO MAKE A DIFFERENCE

DEAR HOPING:

This topic is not covered well in most graduate programs. In thinking about your question, I looked online for schools having a graduate science/policy track, and there are some out there (see here). Graduate students now have some opportunities should they decide to pursue science/policy degrees.

But, how do you do this once you are out of school? I have four recommendations in priority order.

Spend time in the policy world. Determine which governmental entities are most relevant to your policy interests, and become involved in their process. In my world, for example, there are multiple entities including federal, state, local governments, and tribes. Become relevant to policy-makers by understanding their issues, questions, and needs, and the deliberative and decision-making processes that they employ. Unfortunately, this time is time away from science, and may not increase your tenure chances, but I believe it time well-spent. But, I have seen other rewards. Those who spend significant time in the policy world tend to be very successful in receiving science funding from those same agencies.

Establish personal relationships. Scientists and policy-makers are humans, and personal relationships are important. I have found that the mutual trust gained through these relationships is essential for your opinions, knowledge, and scientific results to be considered seriously by policy-makers. Talk to other knowledgeable individuals and find out which governmental staff have policy jurisdiction over your areas of interest, and reach out to them individually. Ask them what they need. Tell them what you might be able to contribute to their process. Seek their suggestions.

Learn how to communicate effectively. If you communicate only via complex, jargon-laden scientific documents, don’t expect your science to be used by policy-makers. Although some scientists have innate abilities to communicate effectively to non-scientists, most have to learn this skill. Remarkably, in my brief examination of the science/policy graduate curricula, I found precious few courses in communication. These programs must teach students how to excel in communicating technical information to lay audiences. There is a lot of useful information on this topic from which you can learn.1

Find a mentor and establish your network. President Colden Baxter is telling stories about SFS members who excel in the science/policy arena (see here). Reach out to them. They are passionate about this topic, and would be eager to share their expertise and knowledge. Attend meetings, both in the scientific and policy worlds, to build your professional network and knowledge. Join the SFS Science and Policy Committee.

I am thrilled that you are interested in this topic! Goal #1 of the Society’s 2014 Five-year Strategic Plan in part is to “better position the Society so as to be viewed as a key source for science-based management decisions and to influence public policy and perceptions.” Society members like you can help us to successfully achieve that goal.

1See info at AAAS.org - Public Engagement Activities for communication guidelines and workshops.

The following are two books with good ratings on the topic. The second is by Randy Olson, who gave an impactful keynote address at the 2014 SFS meeting.

Science Communication: A Practical Guide for Scientists

Don't Be Such a Scientist: Talking Substance in an Age of Style

California SFS Chapter annual meeting recap

By Jeanette Howard

Jim Harrington organized a wonderful and comprehensive CABW/Cal-SFS meeting.

The 24th Annual California Bioassessment Working Group (CABW) and 5th annual meeting of The California Chapter Society of Freshwater Sciences (Cal-SFS) was held at the UC Davis ARC Conference Center on October 24th and 25th, 2017.

Over 200 people registered and attended the meeting to learn about the California Rapid Assessment Method (CRAM), updates to the California Surface Water Ambient Monitoring Program (SWAMP) bioassessment resources, and statewide and regional policy updates. There were a total of 23 science and policy presentations from students, post-docs, research fellows, agency staff, NGOs, consultants, non-profits, and specialists. During the SFS session, 14 presentations covered a wide range of topics such as the effect of aquatic plants on temperature, the contribution of flow variability on river metacommunities, and new and emerging methods in stream science.

Mark your calendars for next year’s Cal-SFS / CABW meeting to be held on October 23-24, 2018 at UC Davis. For more information contact Jim Harrington (james.harrington@wildlife.ca.gov). Visit the California chapter webpage if you would like to join this chapter.

SFS Pacific Northwest chapter annual meeting recap

In November, 45 freshwater scientists attended the SFS Pacific Northwest Chapter annual meeting in La Conner, Washington. The event, organized by Francine Mejia and Dorene MacCoy, brought together representatives from local, state, federal, and tribal governments as well as consultants and independent taxonomists. Over 20 presentations covered topics ranging from bioindicators, invasive species, cyanobacteria, freshwater mussels, and degradation of freshwater ecosystems. This diverse group of scientists “wined and dined” at the waterfront La Conner Inn. Mark your calendars for the 2018 Pacific Northwest Chapter meeting in Idaho (location TBD) on November 6-8. For more information contact Dorene MacCoy (demaccoy@usgs.gov)

SFS members participate at National Diversity STEM Conference

By Checo Colón-Gaud

SFS members who helped with booth included Checo Colón-Gaud (lower right, EDC), PJ Torres (center, Early Career Development Committee) and Nick Macias (left, Student Resources Committee). Also pictured is Anita Arenas (upper right) who was representing Coastal & Estuarine Research Foundation (CERF) and Society of Wetland Scientists (SWS). CASS member societies include: SFS, SWS, CERF, AFS, ASLO, PSA, FMCS, IAGLR, NALMS.

For the second consecutive year, members of the SFS Education and Diversity Committee (EDC) in collaboration with nine other aquatic societies had the opportunity to contribute and participate in SACNAS (National Diversity in STEM Conference) by hosting a Consortium of Aquatic Science Societies (CASS) exhibit booth during the conference. SACNAS is the largest diversity in STEM conference in the country and the CASS exhibit booth provides us with an opportunity to connect with a broadly diverse and multidisciplinary talent pool that includes over 4,000 students. This year, we had a chance to interact with students and professionals who wanted to know more about the role of our Aquatic Science societies, our journals, conferences, and in particular opportunities for students as they become part of the membership. The SFS spearheaded the effort by sending 3 representatives (the EDC chair, one early career representative, and one graduate student) to share their experiences as under-represented minorities involved in the multiple societies. We also had a chance to meet with other SFS members who were attending the conference with their students. These efforts are part of the SFS Strategic Plan to continue to diversify the membership by providing opportunities to broaden participation in aquatic/freshwater science.

New special issue out in Freshwater Biology on river network metacommunities

SFS member Jonathan Tonkin (Oregon State University), Jani Heino (Finnish Environment Institute) and Florian Altermatt (EAWAG and University of Zurich) recently published a special issue in Freshwater Biology highlighting the importance of river network structure on biodiversity, particularly through metacommunity dynamics and associated dispersal processes. Bringing together contributions spanning the tropics to the subarctic, and from protists to fish, the special issue provides a broad look at the dynamics that occur in river networks relating to their unique makeup. The 11 contributions cover a broad range of topics including disease spread, biogeochemistry, trophic dynamics and dispersal, employing a suite of approaches ranging from field and lab experiments through to modeling and population genetics.

If you are interested in metacommunities, river networks, and spatial processes, be sure to check out the special issue (here), which came out in January and is entitled Metacommunities in river networks: The importance of network structure and connectivity on patterns and processes.